Javier Álvarez Benedí from Valladolid in Spain is the principal of the Positive SimRacing team, both spiritually as well as functionally; making the team grow with a business-like determination and can-do mentality. And it’s in this role that Javier is hugely influential in tutoring new sim racing talent.

Javier Álvarez Benedí from Valladolid in Spain is the principal of the Positive SimRacing team, both spiritually as well as functionally; making the team grow with a business-like determination and can-do mentality. And it’s in this role that Javier is hugely influential in tutoring new sim racing talent.

What do you do during the day as your full time job?

In the government of the Castile and León region of Spain, I work a lot with people and teams as a strategist on long term plans and future innovations. And I’ve also been a scientific writer for over fifteen years.

How did you get started with Positive SimRacing?

In 2009 I was competing as a driver in Spanish sim racing championships, in sims like rFactor and games like F1 Challenge. Back than many Spanish drivers didn’t speak English, and didn’t have an international orientation, but I could see that sim racing would become an international eSport.

So, in 2012, I started to look for international championships, and joined Formula Sim Racing (FSR), in rFactor. There I found it was very difficult to start a team in that environment, because there was not enough drivers’ market. Basically, three teams dominated the grid and each had about ten drivers, which made very difficult the growth of new teams. But we had a different vision and philosophy: we saw the sim racing as something to be carried out beyond the sim racers, involving the general public and sponsors. Then, I met Jackson Wendt, and we started Positive SimRacing (PSR), maybe against the odds. Around this same time, the Royal Federation of Automobile of Spain hosted a sim racing competition, and we thought ‘let’s use this ‘, so we recruited some drivers from the top ten of that competition.

The first two years were a big challenge, because we weren’t such a strongly bonded team, more a group of drivers. For other teams it was really easy to steal our best drivers. Yet some people stayed and from this we grew into a team, more structured and moving up the ladder.

In 2014 we moved to iRacing, because there was more potential to grow and the competition was bigger. But because only three or four drivers joined the switch, we basically had to start the team from scratch again.

How does a team bond?

Some drivers, particularly young ones, may be very ambitious and don’t want plans spanning multiple years. They want to grow fast and become frustrated if they think they don’t have a good car setup. For them, it doesn’t matter if their driving style still needs work. With people who need results quickly like that, it’s nearly impossible to build a long term project.

But then, there are drivers that think long term and stick to the team. They have what you could call a philosophy, and we build a shared vision for the team. We’re very people focused. For instance, we don’t like to ‘steal’ drivers from other teams, we develop our own drivers. And that’s also why I think the PSR Driver Development Programme (DDP) with VRS is going so well. We invested lots of time in selecting the right people, and collaborating with drivers already in the team. The personal touch is what makes this strategy work.

How can philosophies differ among teams?

Maybe identity is a better word. There are teams who are elite and they only have to call a certain guy and he’ll join. Their main goal is to be at the limit and to win races. Although we won the SkipBarber 2K World Cup and took wins and podiums in other big events, we’re not at that level yet. We want to get there of course, but we need to develop the drivers and that takes time. This is our vision and we want to generate added value this way.

For this, we work together as a team. For instance, if a driver is in P4 and his teammate takes in P1, that’s like a win for both. We don’t have scenarios like Hamilton versus Rosberg in 2015-2016, or Hamilton versus Alonso in 2007. Everybody is committed to the success of the team. The identity and the sense of belonging to a project are essential parts of a team spirit, and I believe this is our niche.

Teams like Coanda don’t have a team manager role. Is this a different philosophy and

do you think one philosophy is better than the other?

I think it’s different, because Coanda may not have anyone in an official team manager role, however, drivers certainly assume leadership. It may not always be one and the same person, but they must have leadership within the team. They may have few but elite drivers, and they seem to aim to be an elite team with only a few elite drivers. A very good model, if you can make it work.

Coanda is perhaps the reference in modern sim racing, and beyond their sportive success and impressive results, their collaboration with VRS in improving the driver development constitutes a huge added value, which should be recognised by all the community.

Could you say you’re like a learning institution? To use an F1 comparison, like the

Sauber team?

Yes, that’s part of our philosophy, and it applies even to non-driving-related learning. I try to pair up Spanish drivers with English speaking drivers, so they learn English. And we focus on driving analysis and collaborations, like with VRS now. We think this is our added value to the drivers and the sim racing community.

How is the VRS DDP programme going?

We had over fifty applications for the DDP, but it was hard to select eight people. So we did extensive interviews and analysed profiles, and it looks like we’ve did a great job. Despite everybody having real life commitments and not always having 100% attendance in the practices or races, we’ve finished with two teams in top ten of the Blancpain Endurance Series.

Now we also have a junior programme with less intensity, and they’re improving at an incredible rate. They’re ready to join the main programme or be reserves (some of them are as fast as the top guys). So yes, I think the programme has gone well, in terms of results, as well as in terms of team building and driver development.

How do you manage that, how time consuming is it?

The management ‘overhead’ is significant. We had to spend a lot of work on this new structure, organising coaching and testing sessions, monitoring every driver individually, with individual meetings. This is huge! Can you imagine eight drivers and another eight drivers in the junior programme. Lots of work involved. But now we’ve appointed drivers as the ‘captain’ for each team, and this works quite well.

What prepares you for managing a simracing team? I mean, there’s plenty of tutorials

on racecraft, but nothing on managing a simracing team.

It’s not just life experience that helps, but also training. I mean, not just to practice and experience, but also through courses. I did this kind of training with my real life. I think my experience from work also helps, working with people with very different backgrounds helped me a lot.

Do you talk to other team managers?

Not really, with a few exceptions. And, until my knowledge, there is no team manager association. There was one in FSR, a team owner association, which is the only example that I know. However, team associations demand a clear common vision and managers working for the benefit of the group, which is very ambitious, if even realistic. So I don’t miss it. However, nowadays we have good contacts with managers of several teams, such as Blue Flag Racing and others. These contacts are usually very beneficial for the course of the competitions.

As the team principal. What do your tasks involve?

Team management is very demanding on time. For example, this morning I was scared to open Facebook, but maybe there are between fifteen and twenty messages. Some weeks I have to devote twenty or thirty hours. It’s like a second job. So we’ve decided we need to make it more sustainable, and that the team mustn’t depend on one person. If I can’t make it then the team shouldn’t stop. Two years ago we segmented the team into small and strongly bonded sections, and so for instance the Skip Barber team is six driver and one manager. I work with the managers, mostly all the time.

They can also work independently. In my dream, I would only decide on the strategy, budget and time. But often you’ve to talk and ask people what they want, and have the opinion of everybody. It’s always a balance between leadership and a full democracy.

What are difficult decisions you have to make sometimes?

To decide to let a driver join when he asks to join the team. When we were small, we always let everybody join. Now we’re careful, not to upset the balance. It’s difficult to really analyse someone and to anticipate, because when you say no to a driver you may have lost a good opportunity for the future. But then, if you decide to add a driver and he’s not a good addition to the team, he can upset the balance. So that’s one of the most difficult decisions.

Maintaining that balance can be difficult in another way too. In 2012 we had just started, but our philosophy changed a bit, so some of our core drivers sometimes feel a bit out of the team, and they don’t want to analyse their performance every week. But they still want to be part of the family, not all the new things, so we had to make that compatible with the evolution of the team. We had a lot of discussions to find a solution, so now we’ve started the ‘Positive Drivers Club’.

So what does it mean to you, when one of your drivers succeeds?

Several levels of happiness. First your project is succeeding and you get rewarded for all the work and patience, and also because you see your friends, people that you’ve helped and who’ve helped you, you see them succeeding. Maybe that’s the best feeling in life, when someone achieves something. When it has been a difficult journey, there’s also more happiness.

This applies to simracing, but maybe also to all of life?

For sure! Sim Racing is not only competition. It’s a sport that fosters personal and brain development, and there are scientific journals and that publish the benefits of gaming and development. Also concentration. I can do a race two hours without a mistake. But then I can’t sleep afterwards because my brain can’t sleep. And beyond that, as you say, it’s like everything in life. We put time, money, energy, to achieve something. Achieving something, at the end of the day, is the meaning of life.

What’s your goal looking forward?

For myself, I’d like my role to be less important so I can step back from day-to-day to focus on growing the budget and sponsors. It’s a matter of maturing the team. Now we’re working with the segmentation and managers, and I think in the next few years we can consolidate this.

As a team, we want to be in the iRacing World Championship Grand Prix Series, the Blancpain Endurance World Championship and the Skip Barber 2K Cup. Then we enter the top twenty, go to top fifteen. Maybe those are the last steps for the team, in terms of maturity.

You don’t aim to win those championships?

I think that’s too far. We want to be realistic. We would like that, but it’s too far. We don’t think this will happen within the next three years. For 2018 to 2020, the top 15 is a more realistic target, and later we will go for the top 10. Also, we are not obsessed with that.

VRS is happy to announce our new partnership with Dörr Esports founded in early 2021 by the Dörr Group, one of the biggest sports car dealerships worldwide with brands like McLaren, Lamborghini, Aston Martin, and more in their portfolio. They also have a dedicated motorsports team – Dörr Motorsport – currently competing in the ADAC GT4 Germany as well as supporting a kart team with Kart Republic.

VRS is happy to announce our new partnership with Dörr Esports founded in early 2021 by the Dörr Group, one of the biggest sports car dealerships worldwide with brands like McLaren, Lamborghini, Aston Martin, and more in their portfolio. They also have a dedicated motorsports team – Dörr Motorsport – currently competing in the ADAC GT4 Germany as well as supporting a kart team with Kart Republic. Together with Florian Hasse, Bence Bánki, Michael Rächl and Nico Nünninghoff plus their two real life drivers Christer Jöns and Ben Dörr the team has won two championships including the ADAC GT Masters Esports Championship and the CUPRA SimRacing Series, won multiple races and wanting to expand their team and commitment to different platforms as well.

Together with Florian Hasse, Bence Bánki, Michael Rächl and Nico Nünninghoff plus their two real life drivers Christer Jöns and Ben Dörr the team has won two championships including the ADAC GT Masters Esports Championship and the CUPRA SimRacing Series, won multiple races and wanting to expand their team and commitment to different platforms as well.

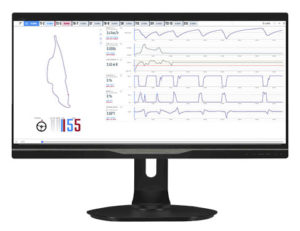

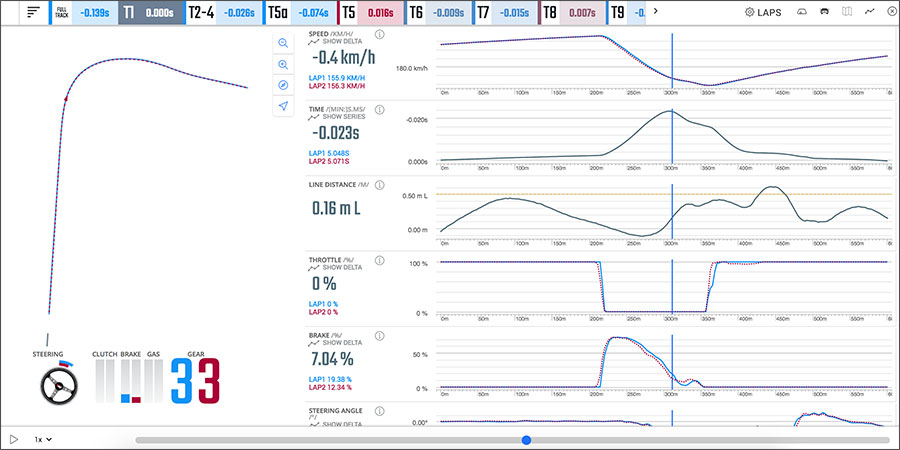

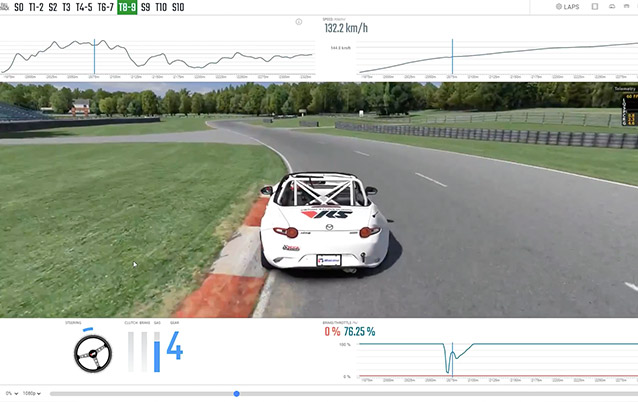

Each VRS datapack consists of data from all relevant iRacing circuits with a setup, telemetry and a replay file from Pro drivers in the current season (Season 3, 2017). With datapacks, you can easily compare your own racing and consequently improve.

Each VRS datapack consists of data from all relevant iRacing circuits with a setup, telemetry and a replay file from Pro drivers in the current season (Season 3, 2017). With datapacks, you can easily compare your own racing and consequently improve.

The differential (or diff, for short) allows the left and right wheels to rotate independently, which helps balance the car through corners. Its configuration determines how much of the torque coming off the engine is transferred to each wheel. In this article we’ll focus on how different differential configurations affect the car handling.

The differential (or diff, for short) allows the left and right wheels to rotate independently, which helps balance the car through corners. Its configuration determines how much of the torque coming off the engine is transferred to each wheel. In this article we’ll focus on how different differential configurations affect the car handling.  A spool gives you good traction accelerating on a straight line, but the handling of the car is compromised during turning. When going around a corner, the outside tire has to travel a longer distance. So, the inside is forced to rotate faster than it needs for the turn radius and hence spins. This causes stress (wear) on both tires and the drive train. In terms of handling, this causes understeer when decelerating, and oversteer when accelerating.

A spool gives you good traction accelerating on a straight line, but the handling of the car is compromised during turning. When going around a corner, the outside tire has to travel a longer distance. So, the inside is forced to rotate faster than it needs for the turn radius and hence spins. This causes stress (wear) on both tires and the drive train. In terms of handling, this causes understeer when decelerating, and oversteer when accelerating.

Javier Álvarez Benedí from Valladolid in Spain is the principal of the

Javier Álvarez Benedí from Valladolid in Spain is the principal of the

Your first week of oval racing is just about the same as when you try anything for the first time, so take it easy! One of the biggest mistakes that rookies make is trying to go too fast, too early. At first glimpse, an oval looks very simple. It’s got a couple straights and a couple long turns. This makes new drivers want to exit pit road and set a world record time on the first lap. However, you’ll soon realize that because the turns only go in one direction, and because the turns are generally longer than those on road courses, that the cars will be set up to only go left, that the car’s setup will be on the ragged edge of spinning out, in order to achieve competitive lap times.

Your first week of oval racing is just about the same as when you try anything for the first time, so take it easy! One of the biggest mistakes that rookies make is trying to go too fast, too early. At first glimpse, an oval looks very simple. It’s got a couple straights and a couple long turns. This makes new drivers want to exit pit road and set a world record time on the first lap. However, you’ll soon realize that because the turns only go in one direction, and because the turns are generally longer than those on road courses, that the cars will be set up to only go left, that the car’s setup will be on the ragged edge of spinning out, in order to achieve competitive lap times.

Meet Tim Ryan: Aussie from Perth, 19 year old, teacher in learning, driver of

Meet Tim Ryan: Aussie from Perth, 19 year old, teacher in learning, driver of