Welcome to the final segment in this four-part series on how to practice efficiently. In this article we will look at the benefits of setting targets for yourself and monitoring your performance.

Welcome to the final segment in this four-part series on how to practice efficiently. In this article we will look at the benefits of setting targets for yourself and monitoring your performance.

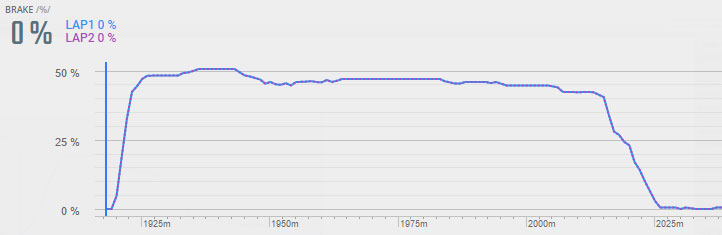

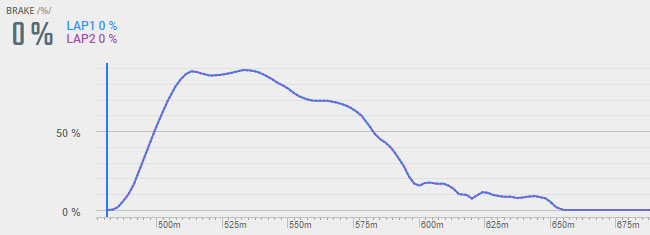

We’ve already discussed the importance of self-analysis in detail, and it’s an excellent idea to make notes during your practice sessions, so you don’t forget things and can give yourself clearly defined targets to work towards. Ideally you should be keeping a log of your progress in various areas, be it braking, concentration, smoothness etc. Perhaps having a rating from 1-10 for how satisfied you are in each area with some optional comments would make sense. This way you could also track your daily / weekly / monthly progress. You could even make reference to specific telemetry session laps and replays you may have saved.

Beginners vs advanced drivers

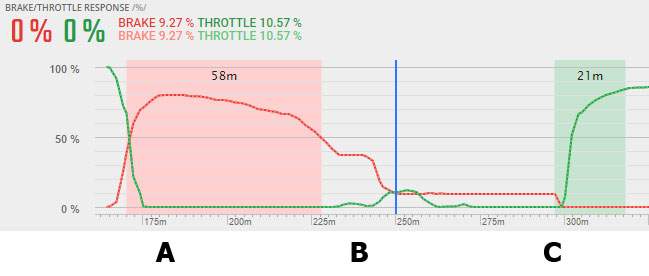

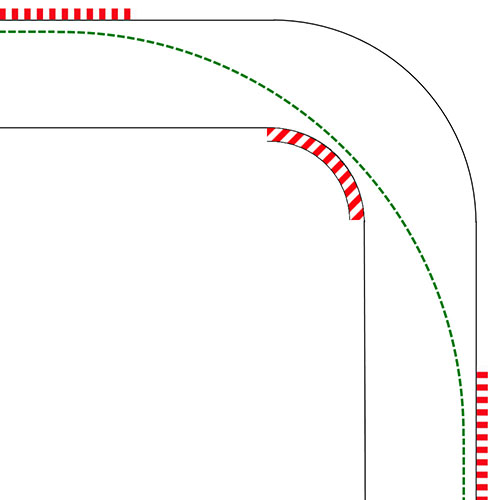

The types of goals and targets you should be giving yourself will vary based on your current experience and skill level. For beginner and intermediate level drivers, your focus should be on more of a driving fundamentals, objective approach. This means choosing categories such as braking points, braking consistency, apex speed, exit speed, line, for which to evaluate your performance.

As your driving becomes more advanced through experience with self-evaluation and analysis, the aforementioned categories should no longer be something you have to consciously focus on in order to understand where you can reduce your laptime. Your focus should instead shift to more abstract goals and targets, such as your breathing, concentration level and vision. We will cover these specific topics in future articles.

Your first self-assessment

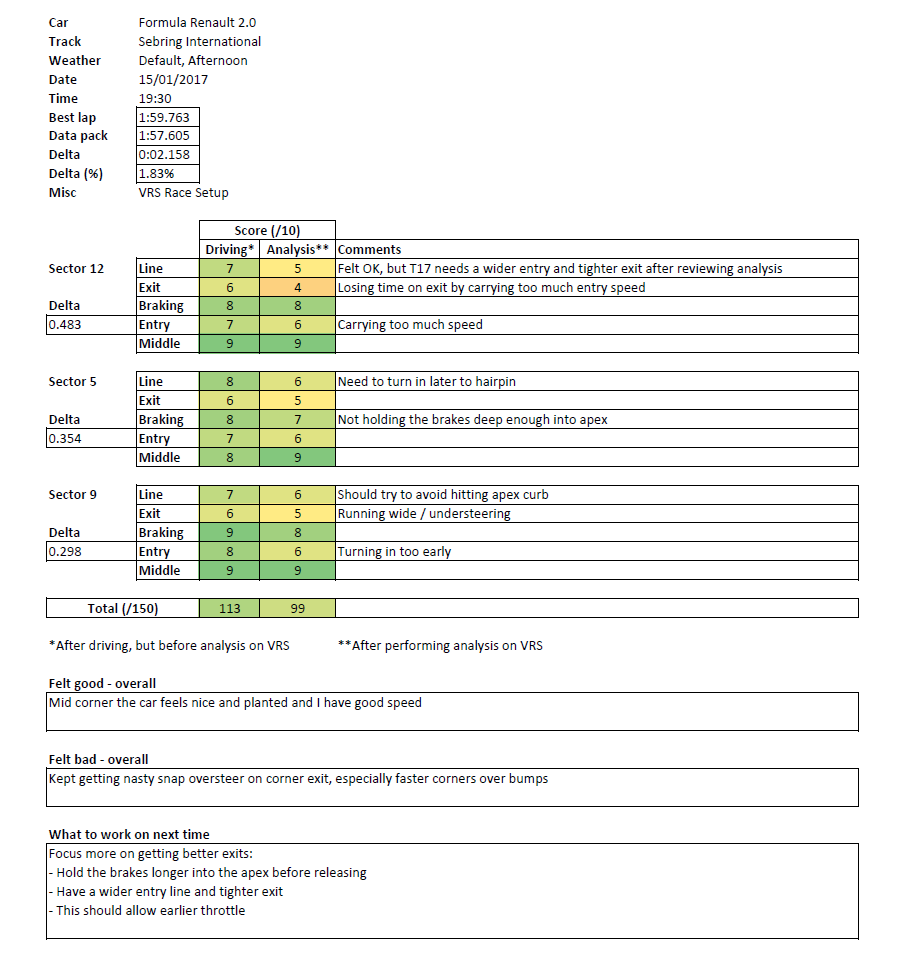

Let’s start from the beginning. Before you’ve carried out any kind of analysis on your driving, it is not sensible to give yourself any targets. It is, however, a good idea to have an evaluation form with a list of performance criteria for which you can rate yourself on after your session. We have provided a template for you:

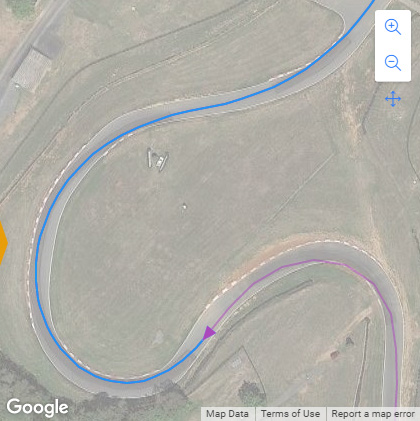

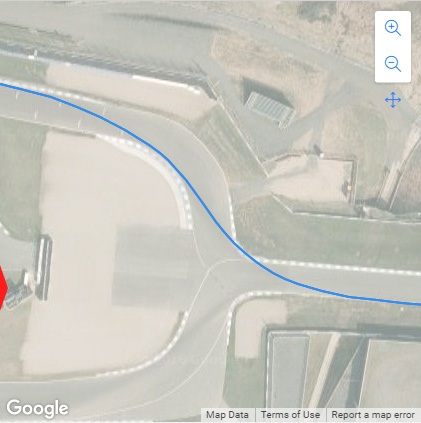

Here we have divided up the driving components for each of the top three auto-generated sectors from VRS, which usually represents a single corner per sector. They are ordered to match the display of opportunities vs target on VRS, where the first one presents the biggest time opportunity to make up and so on.

Each component has a score out of 10 which you give yourself, based on how the session felt. Next to that is the same score, but this time it’s based on what you’ve seen in your driving having carried out some analysis using the tools on VRS. Additionally, each criterion has a field for entering any comments you feel are worth mentioning.

From this information, you should be able to narrow down a few targets to give yourself to work on for your next session, as shown in the example. We recommend keeping this list fairly short so you’re not overloading your brain with thoughts the next time you drive. In the example provided I’ve actually chosen just one target to focus on, which is to have a better exit, and I’ve broken it down into some important and related points.

The immediate benefits of documenting your practice like this are that it provides you with a clearer understanding for where you’re performing badly, and what you should be concentrating your efforts on. Any time you feel like you’re getting lost, or driving without intention, you can just refer yourself back to the notes you’ve given yourself and get back on track.

This document is just an example and a recommendation. By all means feel free to come up with your own version. More advanced drivers may find more value in scoring themselves with different or additional criteria, such as breathing or concentration as touched upon earlier. You might perhaps wish to create a new document for evaluating your performance over a full week, or even a month if you feel like you’ll get better value from doing so.

Tracking progress

Another benefit from recording and logging your performance, especially over longer periods for which you’ve completed many sessions and carried out many self-evaluations, is the ability to track your long term progress in great detail.

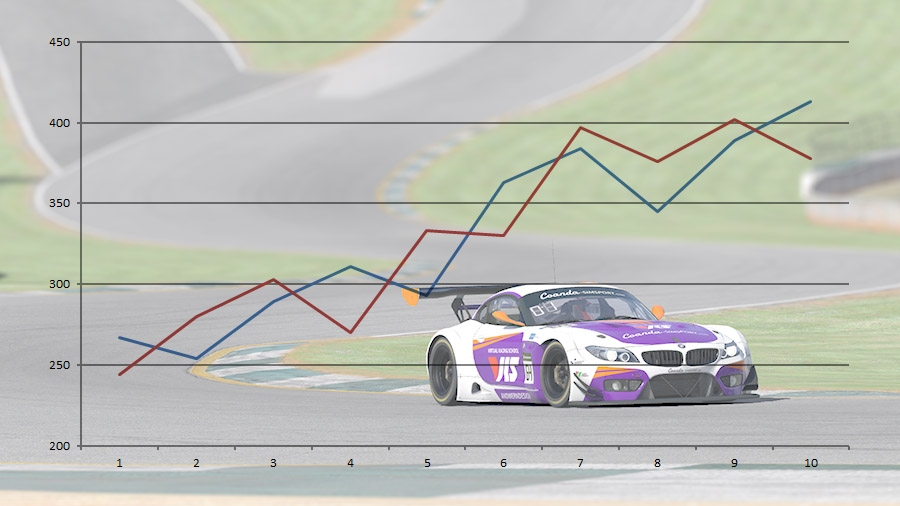

A good way of achieving this is with an additional, separate log, or spreadsheet. Input your scores and time deltas from each session. By tracking your performance over time, you are able to see the exact rate of improvement in specific areas. You will easily be able to identify trends without having to make guesses. Perhaps your corner exit scores are still showing continuous improvement, but your braking scores have been stagnant and need some more work?

If you find that you’ve plateaued in a specific area and you’re still not happy with your performance, it is often a good idea to shift your focus away from that and onto something else. Relentlessly working on the same thing without seeing any further gains is sure to ruin your motivation and may even push you towards giving up altogether.

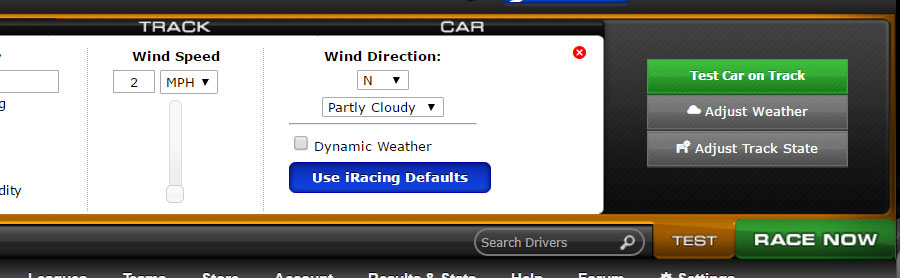

You can also log your race performances in the same way, but include additional variables which may influence your scoring, such as weather, time of day, strength of field. Races also provide many other stats on which to measure yourself including finishing position, incident count, iRating change, SR change. It may even be beneficial to have separate weekly, monthly and even yearly logs which may all identify different patterns.

Up to you

Not everyone will benefit from tracking their driving data in such detail. Some may have limited time available, with other priorities, while others simply want to have fun without expectations. This is perfectly OK! If, however, you are someone who is determined to improve and are willing to go the extra mile to succeed, closely monitoring your performance so you know how best to take the most productive action going forward is sure to help you!

As you progress through your iRacing career, competition is fiercer and you’ll need to use all the tools in the box to find the edge over your rivals. One of these tools is car setup. And while most beginner series have friendly communities with lots of setups being shared on the forums, the willingness to share setups significantly drops off at more competitive series. Especially at the top level of sim racing, setups are seen as highly guarded intellectual property. Thus, having a basic understanding of car setups becomes a very useful asset in your sim racing career.

As you progress through your iRacing career, competition is fiercer and you’ll need to use all the tools in the box to find the edge over your rivals. One of these tools is car setup. And while most beginner series have friendly communities with lots of setups being shared on the forums, the willingness to share setups significantly drops off at more competitive series. Especially at the top level of sim racing, setups are seen as highly guarded intellectual property. Thus, having a basic understanding of car setups becomes a very useful asset in your sim racing career.

Simracing is harsh, and if you expect things to come easily, you’ll be quickly demotivated. Getting good is a long term project that requires time, money and focus. Here are four key areas to keep in mind as you plot your way towards all those simracing victories, which all four have to do with setting correct expectations.

Simracing is harsh, and if you expect things to come easily, you’ll be quickly demotivated. Getting good is a long term project that requires time, money and focus. Here are four key areas to keep in mind as you plot your way towards all those simracing victories, which all four have to do with setting correct expectations. Simracing is brutal. You may think of yourself as a real racing driver, having raced in the likes of Gran Turismo or Forza Motorsport, only to be proven utterly wrong while racing on similar tracks in similar cars in a full-bred racing simulator. Here’s what help you can expect from us.

Simracing is brutal. You may think of yourself as a real racing driver, having raced in the likes of Gran Turismo or Forza Motorsport, only to be proven utterly wrong while racing on similar tracks in similar cars in a full-bred racing simulator. Here’s what help you can expect from us.